- Home

- S Jonathan Bass

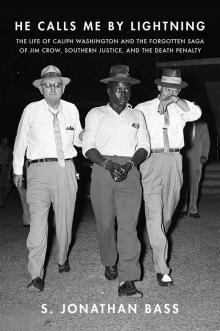

He Calls Me by Lightning

He Calls Me by Lightning Read online

For Kathleen, Caroline, and Nathaniel

CONTENTS

PREFACE

1Steal Away

2A Hell of a Place

3“These White Folks Will Kill You”

4“In Bessemer, Anything Can Happen”

5A “Well Bound Book”

6“Because It Was Self-Defense”

7A Violent and Accidental Death

8“There Are Lots of Ways to Fight”

9“I Just Say I Am Innocent”

10“You Belong to the State of Alabama”

11“Please Spare My Life”

12Called by Lightning

13A Thunderous Arrival

14Whereabouts Unknown

15Sinners to Convert

16Segregation’s Last Stand

17“Sojourn in the Shadow of Death”

18“In a Wasted Land of No Want”

19“He Still Ain’t Dead”

20“Set Me Free Dear Jesus”

ConclusionThe Salvation Club

NOTE ON SOURCES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CREDITS

INDEX

PREFACE

For hardship does not spring from the soil, nor does trouble sprout from the ground.

—JOB 5:6

Muscoda Iron Ore miners in the early 1940s.

SHE WAS ALREADY lying in a coffin in the Bessemer Public Library the first time I saw Hazel Farris. I was on an elementary school field trip to see Bessemer, Alabama’s most celebrated citizen: a leathery corpse known as “Hazel the Mummy.” When we arrived at the city’s library, located in the majestic old post office building on Nineteenth Street, our hosts ushered us down the stairs to the basement and a makeshift “hall of history” where Hazel was lying in state. Never before had I seen a dead body, much less one that passed on over seventy years earlier. As I gazed upon this grotesque artifact—faded ruddy hair, hollow eye sockets, sunken cheekbones, and broken and missing teeth—my thoughts were a mixture of horror and fascination. Her skin looked like an overcooked Idaho potato, and every joint, rib, and bone was visible underneath.

Decades later, when I came across an old promotional poster for Ms. Farris, her image came rushing back, as did the lore surrounding her death. According to the story, she was a pint-sized, red-headed woman in Louisville, Kentucky, who possessed a fierce temper, drank whiskey straight from the bottle, and fought with her husband. At breakfast on the morning of August 16, 1905, she announced her intention to buy a new hat. When her husband objected to this latest spending spree, she pulled a six-gun and shot him dead. As she stood over her spouse’s lifeless corpse and inspected the deed she had done, three city policemen rushed through the door. Farris turned and fired three more shots—killing each officer. Within minutes, a county sheriff’s deputy arrived and slipped into the house. He saw the bodies littered across the floor, and as he tried to sneak up behind Hazel, she turned suddenly, and the pair tussled over the deputy’s gun. His gun discharged, and a wayward bullet tore off Hazel’s ring finger. She soon broke free from his grip, grabbed her pistol from the floor, and ended his life with a single shot.

Hazel Farris fled Kentucky and took refuge among the thieves, murderers, and whores living at the turn of the century in the wild young town of Bessemer, Alabama. She found work in a bordello in the red-light district and a new love—a police officer. It was short-lived, however. When she entrusted her cop-killing stories to her policeman, he opted for the $500 bounty on her head as opposed to her love. Rather than face the hangman’s noose, Farris ended her life with a heady mixture of arsenic and whiskey on December 20, 1906. Her corpse was taken to a local furniture store, where it mummified and was later sold to a carnival show barker.

For over a hundred years, Bessemer residents recounted this sordid tale of Hazel Farris. Few locals, however, asked why a prostitute who murdered five men and took her own life was the city’s most revered and celebrated citizen. The answer was undeniably obvious, even if it was lost upon the city’s white residents: “Hazel the Mummy” was an all-too-fitting symbol of Bessemer—a small industrial town divided by race, labor, and ideology—where an incendiary brew of vice, violence, and corruption thrived. This was a city that counted among its population Communists, vigilantes, black revolutionaries, union thugs, pathological racists, scabs, mobsters, and criminals—all of whom used violence as a necessity to gain or maintain power. And this was a place where crooked politicians and lawless policemen lined their pockets with money and sin, where vice was plentiful and virtue was lacking, where murder and mayhem were essential elements of the culture, and where poor, itinerant individuals like Hazel Farris looked to escape life’s sorrows in a city of strangers.

During the already fractious summer of 1957, fifty years after Hazel’s death, another downhearted resident searched for a way out of Bessemer. His name, unknown to history, was Caliph Washington. Just seventeen, he was the prime suspect in the shooting death of a policeman, James B. “Cowboy” Clark. The racial element to the apparent murder—Washington was black; Clark was white—fueled the sweltering fury of Bessemer’s all-white police force. Most of the city’s population was black, and race only intensified an already omnipresent feeling of danger as the lawmen hunted mercilessly for young Washington. Alone and abandoned, he hid in the woods and prayed for escape.

I first heard of Caliph Washington’s story from David Murphy, who brought a copy of an old handbill to my office at Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama, and smacked it on top of my desk. “You’ve got to read this,” he proclaimed. Murphy, then an undergraduate, was working on his research project for my civil rights history class. In a packet of materials he received from a far-away archive of the Roman Catholic Josephites was a leaflet entitled “Wrongly Condemned Man Held Without Trial.” The man was Caliph Washington. As I soon appreciated, it was indeed a great untold story, but there were, of course, plenty of forgotten tales from the civil rights era that needed telling. I slipped the article into a “future projects” folder and hoped, perhaps, that I would look at it again someday. Someday, however, came sooner than I expected.

One morning as I visited with Reverend Wilson Fallin, a Baptist pastor, historian, and Bessemer native, I asked if he had known Caliph Washington. In his rich, sonorous voice, he answered, “Oh yes,” and proceeded to give me a soul-stirring sermon on Caliph Washington. The minister had known him well and encouraged me to “dig a little deeper” into his tragic experiences. A few days later, Dr. Fallin spoke at St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church in Bessemer, and afterward a small woman walked up to him and said, “You probably don’t remember me, but my husband’s name was Caliph.” Wilson responded, “Of course I remember you, and I know someone that you need to talk to.” The next day I received a message to call Mrs. Washington.

When I spoke with Christine Washington on the phone, she explained that she prayed for many years for someone to come along and tell Caliph Washington’s tale. She paused for a second and added, “I think that someone is you.” And I was taken.

AS I BEGAN to sort out Washington’s tortuous life, I discovered that his story was inseparable from Bessemer—the dark city of “Hazel the Mummy.” Yet I knew that average citizens, both black and white, helped the city maintain a fragile varnish of respectability. These peaceful, law-abiding residents worked hard, attended church, and lived quiet lives. Many were unaware of Bessemer’s shadowy side. “I never knew,” my Pollyannaish mother once told me, “that things were that bad.”

I felt like I was in a slightly privileged position because my parents grew up in Bessemer. During the Great Depression, my grandparents and great-grandparents joined the migration of penniless farmers

looking for a better life and a steady job in the city. My paternal grandfather, Samuel J. Bass, left his father-in-law’s farm in the west Alabama community of Speed’s Mill in Pickens County and found work in the Muscoda Iron Ore Mines on the outskirts of Bessemer. For almost twenty years, he toiled as a miner and safety officer, providing a hard-earned living for his wife Lillian and their three boys. My dad, Sam Jr., was the restless eldest son who escaped Bessemer at sixteen to join the Merchant Marines in 1943. When my grandfather took him to the Alabama Great Southern depot, he bade him goodbye and said, “You are on your own. There’s nothing more I can do to help you.” He turned and walked away as his son stood alone on the train platform. My dad and his brothers were products of the corrupting influences of Bessemer, which left all of them battling personal demons for the rest of their lives.

My mother’s family had a similar background. My mother, Clara Faye, was raised by her grandparents, Collie and Ida Mae Lindsay Burroughs, who left their family’s land in Buhl (west of Tuscaloosa) so that Collie could work as a wrought iron fabricator at Ingalls Iron Works in Bessemer. He had a third-grade education, and could read a little and sign his name, but Ida Mae never went to school and made an X mark in place of her signature. When I knew them, they were well into their eighties. Collie spent his days confined to a wheelchair listening to southern gospel music on an old radio, and when the song and the spirit moved him, he shook in a physical and spiritual earthquake. I often asked him if he was okay, and he always nodded his head, still riding the aftereffects of the band of holy angels who just visited him. His favorite song was Alfred E. Brumley’s “I’ll Fly Away.” Brumley was inspired to write it while he was picking cotton and humming an old prison song, adapting the lyrics to include “When the shadows of this life have gone, I’ll fly away; / Like a bird from prison bars has flown, I’ll fly away.”

BRUMLEY’S LYRICS FORESHADOWED the life and trials of Caliph Washington. Perhaps only in the dim shadow of death could he find a way home. As a young black man in the South of the 1950s, Washington found that the entire legal system—from local law enforcement to the Alabama Supreme Court—was stacked against him. Researching his hopeless cause, I discovered numerous personal connections with his story. Just like my white grandfather, Caliph Washington’s black father moved from rural Pickens County to work as a miner in the Muscoda Mines, where they both joined the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers. Before joining the police force, Cowboy Clark worked, in fact, at Vanderburg’s Gulf Super Hi-Way Service Station, where my uncle, G. W. “Dub” Burroughs, was the manager. When I asked Uncle Dub about Clark’s death, he remembered that “he was killed by a retarded Negro.” Dub’s wife, my aunt Dorothy, was working the graveyard shift at Bessemer General Hospital the night the ambulance brought Clark’s mortally wounded body to the emergency department. She recalled, “He was already dead when he arrived.” And finally, I once worked at a small newspaper in Bessemer where a retired police officer, Lawton Grimes, Jr., served as a photographer. He gained his photo experience by snapping mug shots of prisoners, including Caliph Washington. Lawton spent every workday at lunch regaling us with his exploits on the Bessemer police force and those of his legendary father, Lawton “Stud” Grimes, Sr.

Although these personal connections add authenticity to the story, the broad historical significance of Caliph Washington’s life and trials serve as an avenue to explore the measures used by white southern officials (lawmen, lawyers, judges, and juries) to enforce Jim Crow “justice” at the local level, especially through race-based jury exclusion. The broad focus of this book is on the search for racial justice and the equal application of laws in southern courtrooms, prison systems, and death chambers throughout the civil rights years (1957–72). Thousands of pages of trial transcripts and other legal documents provide unique insight into the southern legal environment from local, state, and federal perspectives. What is missing from the study of southern legal history during those years is a thorough examination of the workings of local- and state-level Jim Crow legal systems. This book is intended to help fill that void.

He Calls Me by Lightning then becomes, in many ways, Bessemer’s story. Caliph Washington’s life has come to symbolize the violence, corruption, and racism that dominated not only in this city but also in the larger South. Bessemer in particular was a worn-out, dirty city, whose most famous inhabitants included “Hazel the Mummy”; Virginia Hill, a Hollywood socialite and girlfriend to mobster Bugsy Siegel; and Joseph N. Gallo, the consigliere (counselor) to the Mafia bosses in New York’s Gambino crime family. But Caliph Washington, a barely literate black man, remains the central character in this forgotten saga of Jim Crow, southern justice, and the racial implications of the death penalty. As one of Washington’s friends once said, “Each and every one of us [should] remember that Caliph Washington is not just a name on a piece of paper or the central character in a story we’ve been told. Caliph Washington is a human being! And every human being deserves . . . honest thought and consideration.”

HE CALLS ME BY LIGHTNING

1

STEAL AWAY

Seventeen-year-old Private Caliph Washington escaped Bessemer in 1955 and served a tour of duty in the U.S. Army.

CALIPH WASHINGTON STARED out the window of the Greyhound Scenic Cruiser as it rolled through bare Mississippi villages like Hickory Flat, Pott’s Camp, Pumpkin Center, and Myrtle. This undisturbed Sunday morning, July 14, 1957, found a handful of quiet passengers scattered about the bus, a General Motors creation with an air-suspension ride and a sputtering air conditioner. A seventeen-year-old army private of average height, Washington had athletic shoulders, a gentle voice, and a sunshine grin that seemed all the brighter against his midnight black skin. Wearing wine-colored pants, a blue shirt, and a fuzzy gray wide-brimmed fedora too small for his head, he sat in the second to last row of the bus, near two other black passengers. A crumpled brown paper sack rested at his feet; it contained a change of clothes, a piece of cake, and a pearl-handled revolver that had just ended the life of a white Alabama policeman.

Over forty-eight hours earlier, just after midnight on Friday, July 12, a shooting incident occurred on an empty red-dirt street close to a row of run-down shotgun houses in Bessemer. Situated thirteen miles southwest of Birmingham, at the base of the red iron mountain that gave it life, Bessemer was a poisonous city consumed by vice, violence, and vigilantism, where an impoverished and powerless black majority was oppressively governed by a ruthless and corrupt white establishment. The shooting of policeman James B. “Cowboy” Clark looked like a homicide, and all evidence pointed to Caliph Washington as the triggerman. Before the shooting, the officer was in high-speed pursuit of a car driven by Washington. That car, left abandoned near the body of the officer, belonged to Washington’s father. The few witnesses all agreed that the man fleeing the murder scene looked like Caliph Washington. From the time of the incident on Friday night, Washington eluded law enforcement officials. As police conducted an aggressive search for the armed fugitive, he slipped out of the state and caught the Greyhound leaving Amory, Mississippi, for Memphis.

Fear and instinct compelled him to run; the time and the place convinced him to escape; life’s experiences and his family’s history whispered for him to steal away. “Steal away in the midnight hour,” urged the old spiritual. “Steal away when you need some power; steal away when your heart is heavy; steal away.” Washington needed the big wheels of that silver Greyhound to take him a thousand miles away from Bessemer to the distant hope of freedom.

IN THE ALABAMA of 1957, Washington’s alleged crime was the “supreme offense, on the same level of a white woman being raped by a black man,” one sheriff’s deputy noted. Such crimes, whether committed or not, collided with long-standing regional, state, and local racial codes of honor, shame, mastery, masculinity, and power. As historian Pete Daniel observed, “At any point, at any time, in any town, crossroads, house, or field, a short circuit in racial custo

ms could spark violence.” The ordeal of Caliph Washington reveals the savage and petty tyranny of law enforcement, criminal jurisprudence, and community vengeance in the Jim Crow South. In what would become a grim, decades-long odyssey, state and local officials ignored the Bill of Rights and denied Washington due process and equal protection. “The entire system of white supremacy,” as author Stetson Kennedy noted in 1946, “is predicated upon prefabricated prejudices against social equality, against which white southerners have been conditioned to react emotionally instead of rationally.”

As Caliph Washington left Alabama on that Sunday bus, he could not escape this burden of irrational southern honor. It was a tangled society, as author Robert Penn Warren once explained, akin to a giant spider web, where even the slightest touch sent “vibration ripples” to the farthest reaches. “It does not matter whether or not you meant to brush the web of things,” Warren wrote. “Your happy foot or your gay wing may have brushed it ever so lightly, but what happens always happens and there is the spider, bearded black and with his great faceted eyes glittering like mirrors in the sun, or like God’s eye, and the fangs dripping.” Washington’s actions sent ripples to farthest corners of white society in Alabama. At worst, he murdered a police officer; at best, he dared to defend himself against a white man. Both would elicit rage and demand eye-for-an-eye vengeance. Caliph Washington’s Alabama tragedy was similar to the Scottsboro Boys case a quarter century before, in which the southern justice system also “proved impotent.” In that case, an all-white jury convicted nine young black men of raping two white women without any evidence that linked them to the alleged crime.

BORN ON NOVEMBER 14, 1939, Caliph was the sixth of eight children for Doug and Aslee Washington—sharecroppers working a tiny strip of bottomland near rural Aliceville, Alabama. Instituted after the Civil War, sharecropping was a form of modern feudalism where poor, landless blacks and whites farmed lands owned by other men. At the end of the season they gave a percentage of their harvest in return. Like many other poor people in Alabama, Doug Washington toiled each day raising cotton for a tight-fisted Pickens County white landowner. The family lived in a cropper’s shack with no electrical power or indoor plumbing, but plenty of rotten boards; the family, as one observer once noted, “could study geology through the floor, botany through the walls, and astronomy through the roof.” The landowner provided the Washingtons with the necessities for planting a cotton crop: an old mule, a rusty plow, and a sack of seeds—nothing else. At picking time, each family member, including young children, had to do their share of the back-breaking labor, with little respite even from the day’s end or stormy weather.

He Calls Me by Lightning

He Calls Me by Lightning